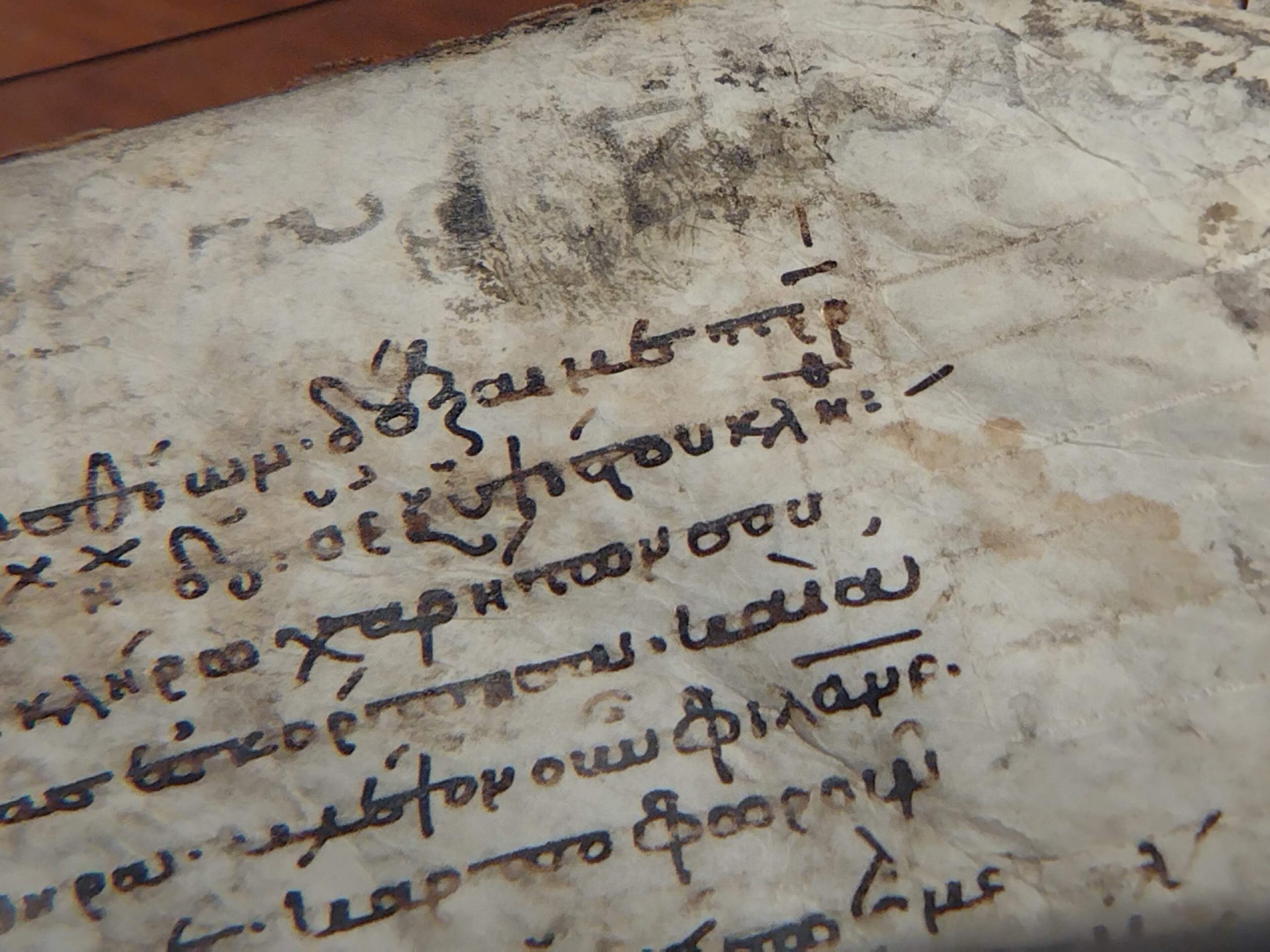

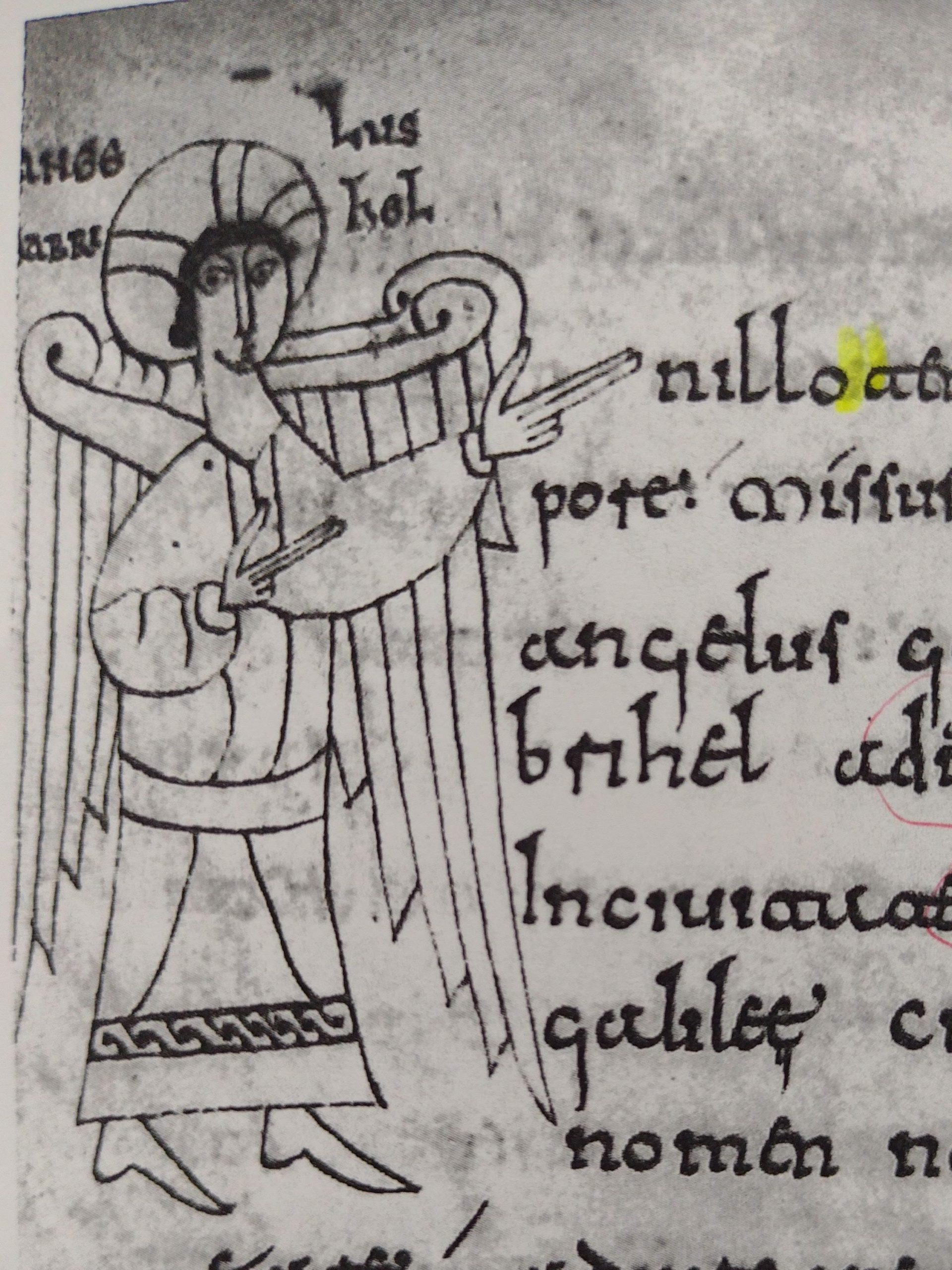

So many of my friends were long dead before I was ever born. I interact with them through their words, left behind. Some of them are mysteries: their treasures, their thoughts, might come down to us with no realistic name attached. Some of them left copious notes, thousands of pages, which I will never finish reading in my lifetime. Some of them left only scraps, squigged in the margins of a manuscript. But they are, indeed dead. But what is true of most of these friends, at least from their writings, is that they thought a whole lot about death before it came for them.

There are, remarkably, people who do not think much about death. A survey by YouGov of British people found that 4% of their respondents never think about death, and another 7% think about it less than once a year. Only 29% of their participants said that they think about death at least once a day or a few times a week – the rest think about it only a few times a month (24%) or a few times a year (27%) or less. All this seems to be true despite reports of wars, natural disasters, diseases, and climate change that are constantly being reported on.

Contrary to my expectations, the highest population who reported never thinking about it were men over 60, where 8% said they never think about death. Both women over 60 and younger men think about death more – only 2% of those women and 4% of young men never think about death. The group who thinks about death the most? Women, age 16-24, where only 1% never think about death and 14% think about it at least every day.

A poll of Americans by CBS news says that most Americans (54%) don’t spend much or really any time thinking about their own deaths. This translates, in the American case, to a lack of preparation: 60% of Americans surveyed said they don’t have a will, including 38% of those 50 and older. As the Onion satirically put it in 2018, “Report: Most Americans’ Retirement Plans Consist Of Hoping Their Random Junk Turns Out To Be Collector’s Item Worth Millions”. It is a bit wild to me that we can hear about floods and humanitarian crisis DR Congo, typhoons in the Philippines, civil war in Myanmar as well as shootings, natural disasters, preventable deaths etc here in the US and not see how fragile our lives are.

Many of us are not people ready to think seriously about dying. Even religious people – while the YouGov survey found that religious people were more likely than their secular peers to think about death once a day (13% to 8%), it’s still not even most of us.

That is not to say that religious people are in no way different from our secular peers in how we think about death. One study, for example, found that religious people were less avoidant of reminder of death than their secular neighbors. Another study, this one in the US, found that some types of religiosity mitigate harm to self-esteem after exposure to reminders of death. A third study found that belief in God and belief in the afterlife were correlated with more death acceptance and less death anxiety.

But still, all those studies are grounded in a framework that assumes part of what religion does in society is mitigate existential terror of death, to bolster our unconscious defenses against the anxiety those subtle reminders of death produce in us. This has been the predominate approach in psychological research – but it fails to take into account that mortality awareness can have both positive and negative effects on people. Sometimes, awareness of death sparks defensiveness in us, other times is sparks prosocial change. Death is complicated, and awareness of our own mortality is similarly complicated and hard to measure.

But what if our very fear of death is a testimony that we were made for something more? Death is natural, but Not everything that is natural is good – God’s work among gentiles indeed intervenes in what is “natural”, namely grafting in non-Israelites to the olive tree, the salvation of humanity. As Romans 11:24 says “For if you have been cut from what is by nature a wild olive tree and grafted, contrary to nature, into a cultivated olive tree, how much more will these natural branches be grafted back into their own olive tree.” This fear of death in us is a visceral reminder to all humans that what is natural is not what is good, and that we require some intervention against nature as it stands now.

Romans 8:20-23 says the creation was subjected to futility, not of its own will, but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its enslavement to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. We know that the whole creation has been groaning together as it suffers together the pains of labor, and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly while we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies.

When we and creation groan, we must not forget what it means. This is not where we belong, as terrifying as it can be, things as they stand are not right. We are waiting for the redemption of our bodies, and for all creation to be free from enslavement and decay.

We are a people sick for eternity.

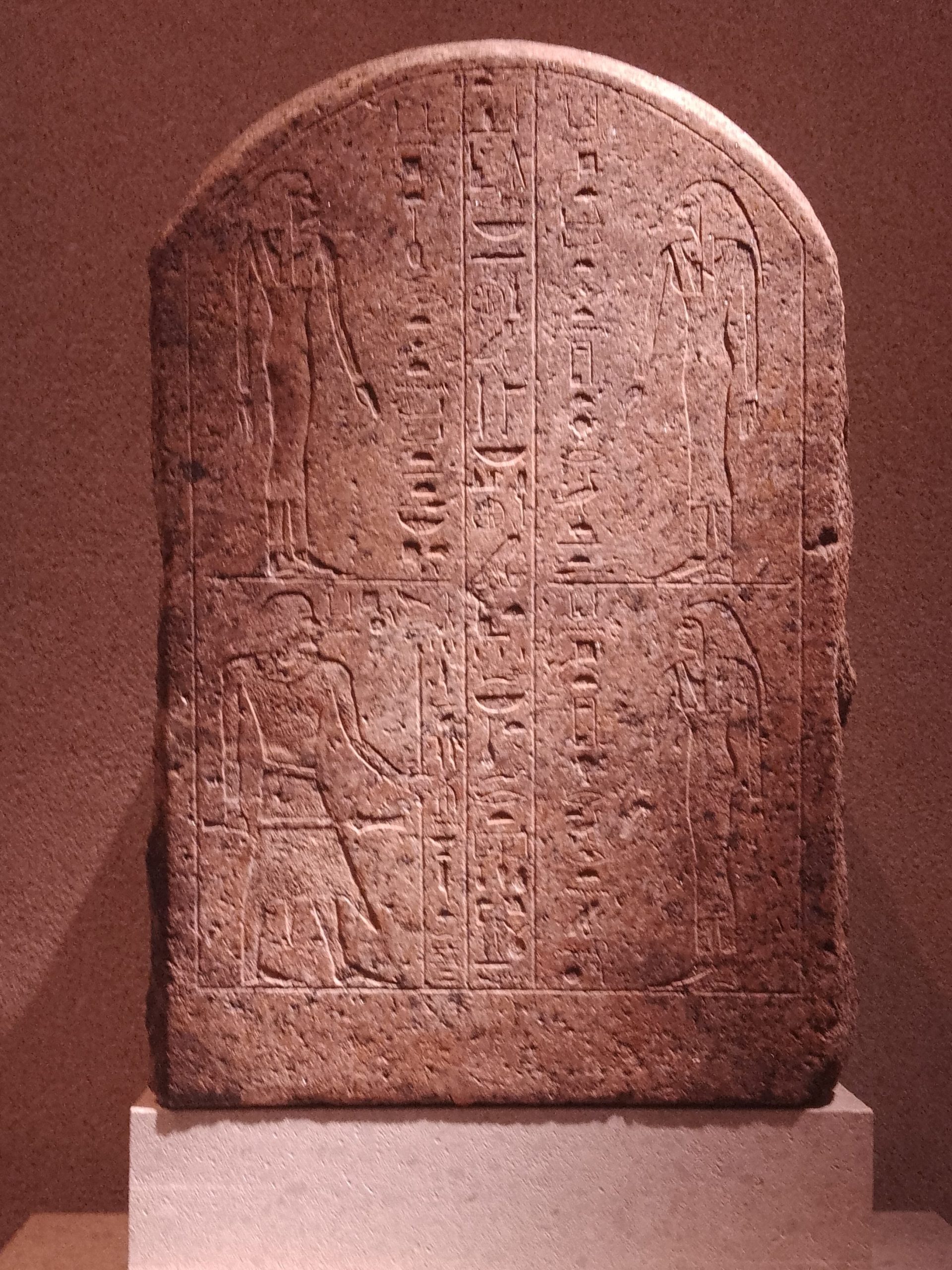

So many of my friends were long dead before I was ever born. And in 200 years, even the babies born when I am 100 years old will be dead. My whole cohort on earth – from the oldest person alive the day I was born to the infant born at the moment of my death – will be in the ground again. Soon, no one will have been alive for Trump’s second presidency, or for World War II, or for the moon landing just the same as no one now was alive for the Incan Empire or the time when Cahokia was inhabited or when the pyramids were built.

Psalm 90:3-6 says You turn us back to dust and say, “Turn back, you mortals.” For a thousand years in your sight are like yesterday when it is past or like a watch in the night. You sweep them away; they are like a dream, like grass that is renewed in the morning; in the morning it flourishes and is renewed; in the evening it fades and withers.

But still yet, after the darkest season of the year (Advent), a child is born to us. Year after year, this baby is born among us – a small and miraculous in-breaking of that eternity for which we were made.

Subscribe Below!

Leave a Reply