(Monothelitism, part 3 – how it ends – see part 1 and part 2)

“Therefore, my beloved ones, the end- times have arrived,” wrote one anonymous Byzantine in the 640’s (Homily on the End-Times, trans. Shoemaker).

But wait, you should be saying, I thought we already did this back in 614. The end times were averted for the Byzantines, they won…right? Why are they sounding the alarm about the end of the world, AGAIN?

We last left Heraclius and the Byzantine Empire in a state of triumph, with a hard-won and very fragile peace among the churches less than 10 years ago. The Pope, the Armenians, Antioch(ish), Alexandria, and Constantinople seemed to finally be on the same page, united around the idea of one will in Christ. Only Jerusalem’s Patriarch seemed to have reservations, and those were largely silenced.

How did it all fall apart so fast?

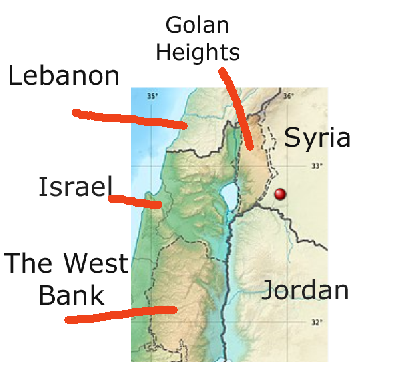

But unknown to Heraclius, something had been stirring in Hejaz, in Arabia. I cannot tell you when the Byzantines first took notice of this new force, but by 636 (four years after the death of Muhammad), the Byzantines lost their first battle to the Caliph’s army. This was the Battle of Yarmouk, near Damascus. The Byzantines lost Syria, and this time for good.

Sometimes I like to image Heraclius, sort of like Kate McKinnon’s Hilary Clinton after the 2016 election, singing “Hallelujah:. Now song lyrics are very copyrighted, so here’s the song: but especially the last verse. Heraclius did his best. It wasn’t enough.

But wait, you might be asking. I thought we were talking about Monothelitism, the compromise between all the arms of the Church where everyone could agree that there is one will in Christ. How does that relate to the rise of Islam? What does the Battle of Yarmouk have to do with the end at this last big imperial push for Christian unity?

The credibility of Heraclius’s theological position was, in the eyes of the movers and shakers of the Byzantine world, intimately tied to his military success. God was clearly on his side when he was a winner. Yes, he had had his detractors including the Patriarch of Jerusalem Sophronius, but they stayed quiet (more or less). When that Sophronius and his disciple (one Maximus the Confessor) tried to agitate, they were outvoted by other Patriarchs and suppressed. In 634, Sophronius writes:

“I accept those who whom they accepted and received gladly, and I anathematize, and I reject whomever they subjected to anathema and considered rejected from our catholic and holy church” i.e. the Miaphysites and the members of the Church of the East, with whom Monothelitism was trying to find union. (Synodical Letter 2.5.1, trans. Allen) He calls Miaphysites “the promoters of godless confusion” (Synodical Letter 2.3.9) and lists their believes among the Big Bads of Christian history – the Messalians, the Tritheists, the Marcionites, the Montanists, etc, and says “I also anathematize and condemn also all who think like them, those who vie with them in the same impiety and have died unrepentant in them and those who even at the present time still persist in them and fight the preaching of our catholic church and trike our right and blameless faith.” (Synodal Letter 2.6.4).

It should be abundantly clear from these snippets that even before the rise of Islam, Sophronius does NOT want to work with the Miaphysites. He is not interested in union with them. He sees the imperial policy as problematic, both because he has issue with the idea of one will/operation (something he discusses in his letter in 634 we are still talking about operations) but also because he does not want to have to deal with these impious people descended from Simon Magus himself (cf. Synodical Letter 2.6.1; Acts 8).

But while the emperor is winning, Sophronius has to shut up and those following him like Maximus need to stay quiet too. More or less, they followed imperial policy while it seemed the empire was politically strong. But then Jerusalem is under siege, and Christians are crying once again that it is the end of the world. One Life has the saint explaining “the shaking of crosses means many pain and perils: it means instability in our faith and apostasy….universal destruction and captivity….the fall and perturbation of the empire, and very difficult times and circumstances for the state. Further, it plainly shows that the arrival of the Adversary is at hand.” (Life of Theodore of Sykeon CXXXIV, 1.106 trans. Hoyland).

Sophronius knew the cause of this new menace. “If we were to live as is dear and pleasing to God, we would rejoice over the fall of the Saracean enemy,” (Christmas Sermon 515 trans. Hoyland). “Saracean” was the Greek term for group that emerged out of Arabia, the Caliph’s army. What is it that Christians are doing that is so displeasing? Sophronius explains:

“But the present circumstances are forcing me to think differently about our way of life, for why are [so many] wars being fought among us? Why do barbarian raids abound? Why are the troops of the Saracens attacking us?… We are ourselves, in truth, responsible for all these things and no word will be found for our defense. What word or place will be given us for defense when we have taken all these gifts from him, befouled them and defiled everything with our vile actions,” (Holy Baptism 162, trans. Hoyland).

What are these vile actions? Turning away from the Orthodox faith – “Therefore, if we would do the will of his Father, having the true and orthodox faith, we should blunt the Ishmaelite sword and turn away the Saracen dagger and shatter the Hagarene bow,” (On the Nativity 27, trans. Shoemaker).

Sophronius, this pesky Patriarch of Jerusalem who never wanted to get along with the Miaphysites anyway, dies in 638. His disciple, Maximus the Confessor, takes up the call to fight this forced cooperation. He writes against Monothelitism specifically, but also redoubles on his critique of the non-Chalcedonian “heretics” who he does not want to work with. He also sees the arrival of the Muslims as heralding the “arrival of the Antichrist” (Letter 14, trans. Shoemaker). In a “record” of Maximus’s trial, Maximus says “No emperor was able to persuade the Fathers who speak of God to be reconciled with the heretics of their times by means of equivocal expressions,” (Record of the Trial, 5, trans. Allen & Neil). The message is clear: emperors should not try to force reconciliation with heretics. The results were disaster.

Heraclius’s fragile union did not stand a chance.

Maximus took up the yoke from Sophronius and redoubled his efforts to destroy Monothelitism and end the hard-won but short-lived union between the churches. And he was largely successful. In 638, the Pope who had supported Heraclius died, and the next popes, saw that their theological rivals as impious and full of contagion – like Maximus and Sophronius. It did not take much for them to connect the political atrocities and the loss of Jerusalem with the fact that they had been taking communion with impure/impious Christians.

So in 638, the world ended again.

The Byzantines lost Jerusalem.

And Heraclius’s attempts to hold together Christians who fundamentally did not like each other ended the way all previous imperial attempts at creating unity did – in failure.

So ended the last pre-modern attempt to unite the Church.

***

Monothelitism: why do we care about a failed compromise by one 7th century emperor?

In these last three posts, I have covered the rise and fall of Heraclius’s attempt to force the church together. Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Theologians have generally followed Maximus, in saying the failure was primarily a theological one: for good Chalcedonians, Monothelitism was just Miaphysite belief in Chalcedonian clothing and with deceptive anathemas against Severus. But I am deeply indebted in these posts to the work of Phil Booth and his Crisis of Empire: Doctrine and Dissent at the End of Late Antiquity – who grounds the theological debate in the social and political situation of late antiquity. My contribution here is to look at last attempt at compromise as one in a series of imperial attempts to bring the church together. I hope that, after reading these posts, you have more of an idea of what ecumenism meant in the late ancient Christian world. I hope also that this can spur us today to think seriously about what it means for Christians to work together after two-thousand years of vitriolic strife.

***

Bonus:

We have both the advantage and disadvantage of time and distance, so let me try to align some dates to show the convergence people might have been feeling:

| Year | Byzantines | Muslims |

| 610 | Heraclius seizes the Byzantine Throne | Traditionally, Muhammad, 40, is visited by the angel Gabriel, who recites the first revelation of the Quran |

| 622 | Heraclius begins his counterattack against the Persians | The Hijrah, the birth of Islam |

| 633 | Egyptian Christians forced to take communion together | Muhammad dies |

| 638 | Sergius, Sophronius, and Pope Honorius die Phyrrus, who supports Monothelitism, becomes Patriarch of Constantinople | The Caliph’s army conquers Jerusalem Arabs begin conquest of Egypt |

| 641 | Heraclius dies and there is a succession crisis (4 emperors in 1 year!) Persian Empire falls | The Caliph’s army finish conquest of Egypt |

| 654 | Pyrrhus returns to the patriarchal throne after being ousted in 641 | The Caliph’s army (and allies) siege Constantinople |

Leave a Reply