(Monothelitism, Part 2 of 3)

For the context and my first post on Monothelitism, see here.

As far as the Romans were concerned, there was more than an incidental connection between the divine and mundane boundaries of the roman empire: God had, in fact, revealed the proper boundaries of the empire to Constantius II (d. 361). Territory was not some theoretical thing, it was a divine mandate. And yes, territory had been swapped back and forth with the Persians for a few hundred years, and yes the Western Empire had fallen, but that idea of divinely appointed boundaries remained – and Heraclius had to get Jerusalem back from the Persians. He rallied his forces and began his counterattack in 622. Further south that same year Muhammad left Mecca for Medina and Islam was born.

Things got worse before they got better for the Byzantines: in 626, Constantinople itself was sieged and Heraclius (with an empty treasury from a costly war) was begging the Church for money. But long story short, Constantinople survived the siege and in 628, Heraclius triumphed against the Persians. The Byzantines got back the True Cross. Happily ever after for them (and sad times for those, like the Jews, who particularly suffered under their rule). The Empire was intact again, as God (via Constantinus II), had ordained it.

War over, Heraclius sought to reunite the Church.

Others had tried before him. They had all failed.

Emperors vs the Factious Church

Round I: Constantine the Great (4th century)

Constantine, in fact, held the very first ecumenical council to try to get the bickering factions of Christians lusting after imperial support to get it together and get along in 325. The Arians famously lost that battle to what would become the Orthodox, and the Roman Empire was firmly associated with the results of Constantine’s church council, or so the story goes. But that triumphant narrative of the Orthodox over the Arians leaves out a few key points – namely that it was an Arian bishop (Eusebius of Nicomedia) who tutored Constantine’s children, and advised the royal household. Further, this same Arian is the man who baptized Constantine on his deathbed – a fact that Orthodox historians tried to write out of history. Further, Constantine’s successor, Constantius II (familiar from the last paragraph) actively supported the Arian group – a support that did not waver until the end of Constantine’s dynasty. It seems that Constantine did not try to stomp out the Arians as much as try to maneuver both the Orthodox and the Arians. Nicaea, for him, might have been about theology (we don’t really know and he wasn’t even a Christian at the time he presided over it) – but it was definitely about trying to get this factious Christians to get along please.

Heraclius was trying, where Constantine had failed. But there were others, too.

Round II: Zeno (5th century)

Zeno, who reigned from 474 to 491, was a barbarian in the old sense of the word. He was not of royal blood, but instead came from Isauria (in modern southern Turkey). Like Constantine before him and Heraclius after him, he was dealing with civil war, invasions (from the Vandals), and a perplexing amount of Christian strife. Like Constantine before him, and Heraclius after him, after he took care of foreign policy by making peace with the Vandals and the Ostrogoths…then he set to trying to reunite the Church which had never really been united in the first place. The players, this time, were familiar from our story about Heraclius – the Miaphysites (who believed in one nature of Christ), and the Chalcedonians (who believed in two). Unlike Constatine, but like Heraclius, Zeno worked with the Patriarch of Constantinople to publish a document sure to make peace: the Henotikon. The Henotikon said we all love Cyril, Cyril is great, yay! And avoided any definitive statement on who’s interpretation of Cyril was correct, therefore side-stepping the issue of the number of Christ’s natures. Problem solved!

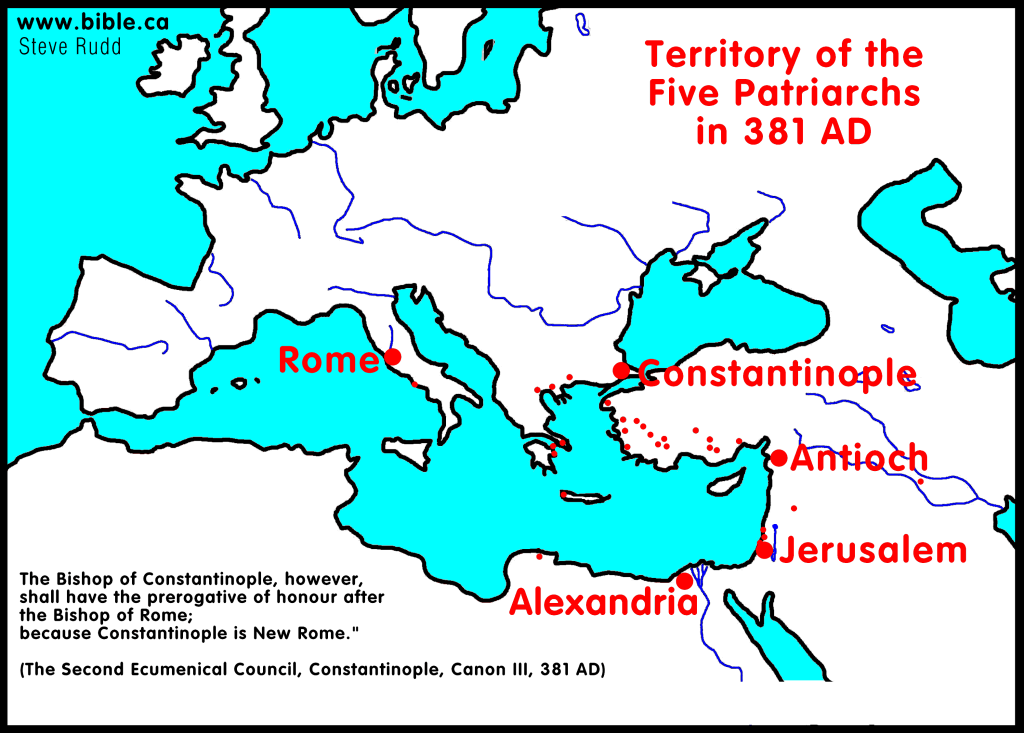

Nope. Problem not solved. Some people got annoyed at how the Patriarch of Constantinople and the Emperor were trying to strong-arm church politics…and Zeno died and the Patriarch got excommunicated and the whole thing ended up cementing a much bigger rift between Alexandria+Antioch and Constantinople+Rome that would not be healed until modern times. Oh well Zeno, it was a good try.

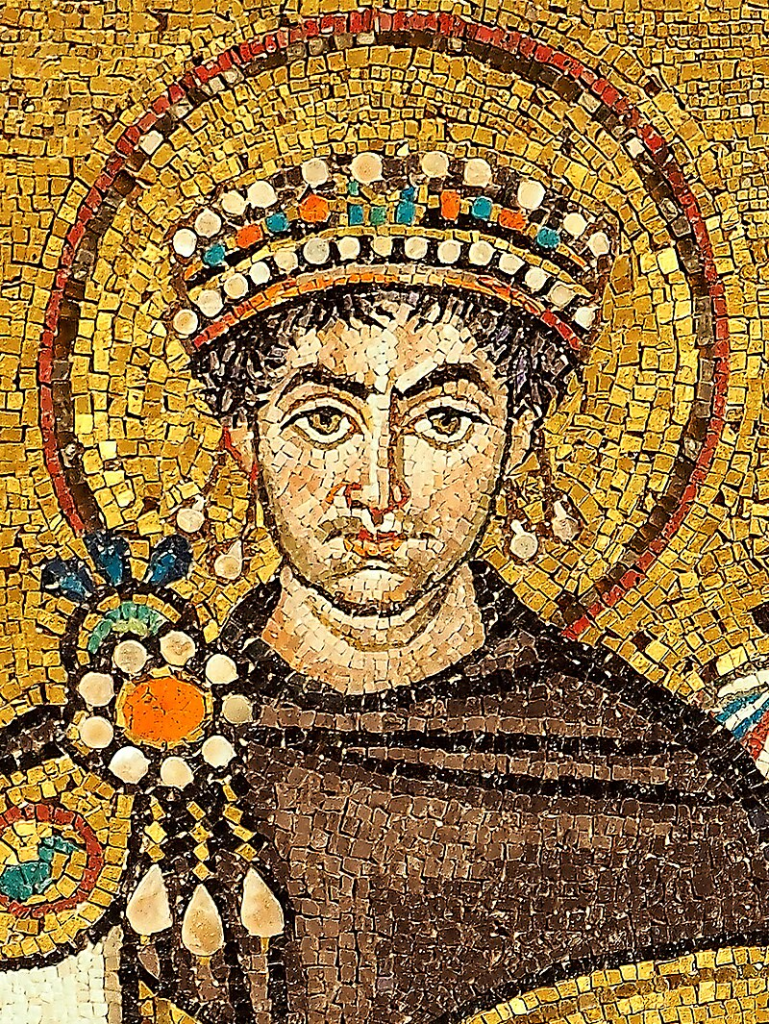

Round III: Justinian (6th century)

The last precursor to Heraclius I would like to address is the Emperor Justinian. Justinian (who reigned from 527 – 565) was NOT playing. He put down revolts. He conquered the Vandal kingdom in North Africa. He reconquered Italy from the Goths. All those people Zeno made peace with? He dealt with them with some wars and won. Contrary to Constantine, Zeno, and Heraclius, Justinian set to trying to reunify the church before he dealt with other matters (and was himself something of a theologian). Early in his reign, in 532, Justinian invited the head of the Miaphysites (Severus of Antioch) and several other prominent bishops to a synod, promising immunity for the attendees of the dialogue. These attempts at parlay between the two sides continued for about years at which point Justinian gave up and said “screw it!” He exiled all the Miaphysites involved in the talks, deposed Severus from his seat in Antioch, and began seeking more authoritarian solutions to his domestic problems.

Back to Heraclius and 628, in the 7th century

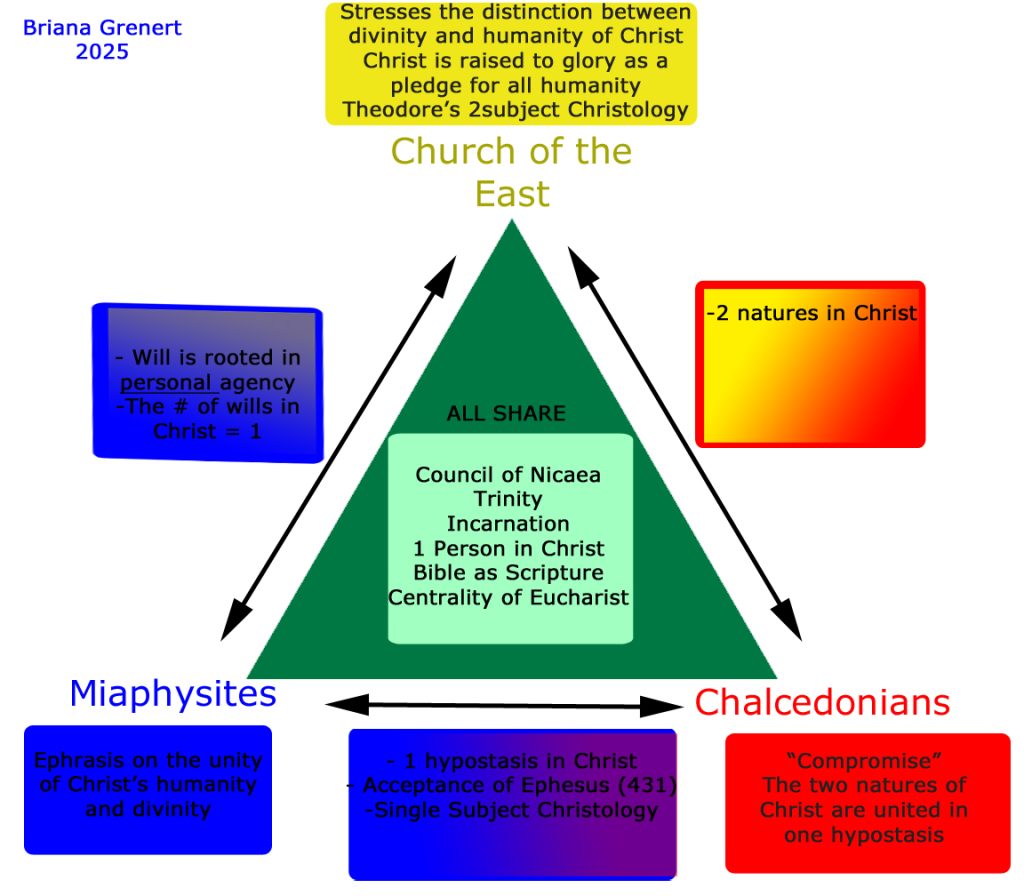

Heraclius then, was trying to do what no emperor before him had ever succeeded in and strongarm unity into the Church. The territory was intact again, with the return of Jerusalem and the True Cross. Like Zeno, Heraclius had a major ally in the Patriarch of Constantinople, Sergius. It was Sergius who used the Church’s money to help fund Heraclius’s wars. They knew it was useless to try to fight over Christ’s natures – people were not going to agree on that. So they set to thinking about what everyone could agree on. I wonder if they made a chart like this one…and then they hit upon it.

What if they said there was operation in Christ! This was something Miaphysites had already discussed, but had not been a point of discussion yet for everyone else. It avoided sticky ideas like persons, natures, hypostases, etc. They could unite these arguing groups around there being one operation in Christ!

They published their idea in 628, and Heraclius began to meet with all parties involved – including the Church of the East (hitherto excluded from this discussion). In 629, he met with the Miaphysite Patriarch of Antioch and by 631 he seems to have had some success coming into Union with him. Around 630, Heraclius met with the Catholicos of the Church of the East in Aleppo, and took communion with him. By 633, Miaphysites and Chalcedonians begin sharing communion together in Egypt, thanks to the efforts of Patriarch Cyrus (enforced by persecutions).

Heraclius was having success never before seen!

The Patriarch of Jerusalem, a staunch Chalcedonian, hated all of this but when Heraclius switched from the language of operations to the language of wills (“One Will in Christ”) he was outvoted at a synod in Cyprus in 634. This is the birth of Monothelitism: the idea that there is one will in Christ.

For one short moment, the Church was united by imperial and patriarchal force around the idea that there was one will in Christ.

Heraclius had won back the holy land and, it seemed, had united the Church. With his military success at the restoration of the empire, who could deny that God was with him?

Who knows, maybe this peace would have held had things been different. But there was already a lot of discontentment. There was that pesky Patriarch of Jerusalem, a very unhappy Chalcedonian who had been outvoted for now but was boiling with dissent. That Patriarch of Antioch who made the agreement with Heraclius died, and the next one was not so keen on continuing the alliance. The Catholicos of the Church of the East who met with Heraclius was met with fierce opposition when he returned home, and many felt that the priest had betrayed them in his Union with the Empire. But still, maybe all this would have boiled down, had Heraclius remained victorious. You can’t argue with someone who averts the end of the world.

But Heraclius was looking many places, but not to the South, to Arabia. He didn’t know that a new force on the horizon. In 632, Muhammad died, and his successors set out to change the world. The Byzantines and the Persians, exhausted from years of endless war, wouldn’t know what hit them.

For how it all fell apart, look forward to the conclusion!

Leave a Reply