(Monothelitism, Part 1 – The Context)

Many people who have studied the history of Christianity have never heard of Monothelitism or the Monothelite Controversy. My students in Church History at Duke skip right over it. At Princeton Seminary, Church History didn’t mention it. I tutored a student at Yale, it wasn’t on their syllabus either.

I am hoping to write a series of three posts about Monothelitism (and why anyone should care about it). This first one is the context behind the controversy. The second is about imperial efforts to reconcile the fractured church. The third is about the fall out from the controversy. I am less interested in the technical theological details, though I will try in brief to sketch those. Instead, I would like to use this attempt at finding unity across the Church through a theological compromise fits into the ongoing story of Christian Unity.

At its core, Monothelitism is about the will(s) of Christ. But also, at its core, it’s a story of a contracting empire – the ending of a world, and the birth of a new one.

One place this story starts is in 610, where the newly minted Emperor Heraclius has usurped the previous usurper to the Byzantine throne, Phocas. He seizes an empire divided and besieged, as well as bleeding from the civil war he helped incite. The Byzantines have been at war with the Persians since time immemorial, and their last conflict is well underway at the same time that the Avar Khangate is on the rise and the Slavs (who first appear on the Roman consciousness a bit earlier, in the 6th century) are pushing deeper into Europe. The Western Roman Empire has long fallen – the last emperor died in 423, Rome was sacked in 455, and now it’s occupied by a bunch of smaller kingdoms (the Visigoths, the Merovingians, Lombards etc).

Unbeknownst to both the Byzantines and the Persians, down in Hejaz in Arabia, something is brewing. 610 is the first year of Heraclius’s reign. It is also, traditionally, the year of Muhammad’s first revelation.

But from a Byzantine perspective, the early 7th century is one of chaos. In 614, just 4 years after Heraclius ascends the throne, the unthinkable happens. The Eastern Roman Empire, which has occupied the Holy Land since before there was such a thing, loses Jerusalem and all Palestine to the Sassanians. Palestine, annexed in 63 BCE, fell to the Persians. Huge parts of the population of Jerusalem are taken into captivity. Many other inhabitants of the city were slaughtered. Further, the relic True Cross is removed.

For many Christian writers, it felt like the world was quite literally ending. And they knew who was to blame – other Christians, who believed the wrong things about Jesus’s nature(s) and so were consecrating polluted Eucharist and quite literally destroying the world.

Another place our story starts is one hundred and fifty years earlier. It’s 451, where the Roman Emperor Marcian had called an ecumenical council of about 520 bishops to settle the problem of a major political dispute between Alexandria and Constantinople as well as the theological issue about Jesus’s nature(s). Nicaea had determined that Jesus is God and Jesus is Human – but how? Did Jesus have some God-Human mixed nature? Did Jesus have a divine nature clothed in a human nature? Did Jesus have two natures that remained distinct and if so how were they united in the one Jesus?

It is no accident that all these bishops are from the Roman Empire and that the emperor called the council – ecumenical did not have the same meaning it has today. Today, ecumenical generally refers to many Christians coming together from different denominations. Even in later Latin and Greek use, it comes to mean “representing the entire Christian world” but it comes from “representing the entire civilized inhabited world” – i.e. the Roman Empire. The Church in Persia did not ratify the first ecumenical council, the Council of Nicaea, until some 85 years after it took place not because they disagreed with it but because they weren’t invited and so didn’t really hear about/get around to doing something with its findings until much later.

The Church’s history is that of a vast network of people all over the world, who were active as far from Jerusalem as China by 635 and who left traces throughout central and south Asia throughout antiquity. The independent Kingdoms of Axum (Ethiopia), Nubia, Georgia, and Armenia as well as the Ghassanid Kingdom (in Arabia) all have their own stories with Christianity that are certainly influenced by the Roman one but often go unnoticed (and in this blog post will continue to do so). The way we teach and tell the story of the Church is from the perspective of the Roman World, in part because even in antiquity, Rome/Constantinople’s reach was so devastatingly wide.

So, as I was saying, the Roman Emperor called a council to settle matters of polity as well as to tackle the question of Jesus’s nature(s).

And when the dust settled, there were three recognizable camps to which all the churches we know today can be classified:

| Miaphysite | Chalcedonian | Non-Chalcedonian Dyophysite[1] |

| One Person, One Nature, One Hypostasis | One Person, Two Natures, Two Hypostases | One Person, Two Natures, Two Hypostases |

| Oriental Orthodox (e.g. Syriacs, Armenians, Copts, Ethiopians, etc) | Eastern Orthodox (e.g. Greeks, Russians, Romanians, etc) | Church of the East (Assyrian Church of the East & Ancient Church of the East) |

| Roman Catholics and Eastern Catholics (Melkites, Maronites, Armenian Catholics, Syriac Catholics etc.) | ||

| Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church | Most protestants | |

| Approximately 50 million members | …about 2 billion members | Approximately 475,000 members mostly in Iraq and India |

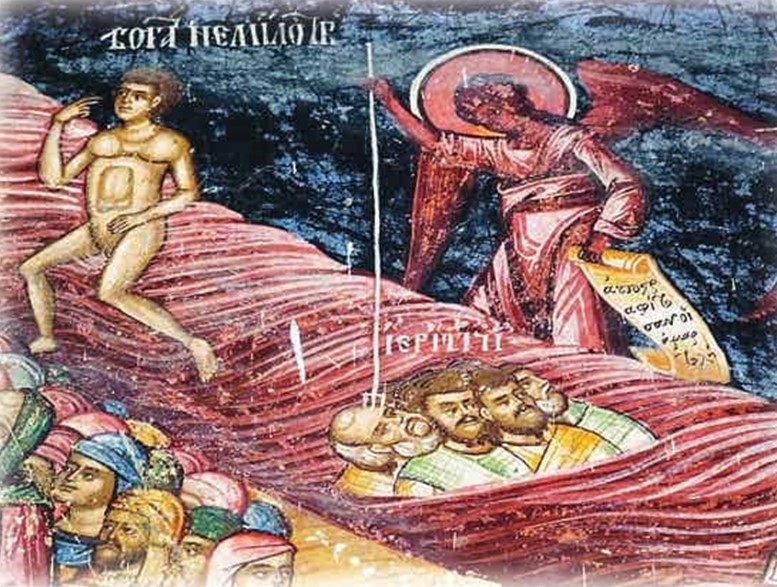

In Antiquity, most of the Non-Chalcedonian Dyophysites were in the Persian Empire. Most of the Chalcedonians and Miaphysites (though not all!) were in the Roman/Byzantine Empire. People had lots of different nuances on these positions. Some groups switched sides – the Georgians were originally Miaphysites, but switched Chalcedonian theology and a union with the Church in Constantinople around 600. But the point is that there were three camps. And whatever Christians on the ground felt about these three camps (if they had any opinion at all), the leaders and writers associated with each of these groups by and large did not like the others. They did what they could to keep their flocks away from the others, preaching vitriolic sermons, drawing paintings of the others burning in hell on their walls, and carefully controlling famous holy sites.

Increasingly, over the painful 150 years that follow, the writers of these three groups became convinced that calamities in the world were caused by the perversion of Christian practice that these wrong Christians were doing. It wasn’t, after a time, just that their ritual were ineffective – it’s that they were demonic.

And it is a church divided that Heraclius seizes when he seizes when he seizes the Byzantine Empire. And when the Persians seize Jerusalem, so long ago seized by the Romans, it is this division that bleeds over the elite Christian discourse.

614 is the year that the world, in some sense, ended for the Byzantines. If Heraclius wants to heal the Empire, then, he has two problems: the war, and this 150 year-old-wound. Other emperors, notably Zeno and Justinian, had tried to preserve the empire and unite the Church – but had only ever succeeded in one of these things. Would Heraclius do better, and succeed where all others had failed?

And don’t forget about Hejaz. The Persians and the Byzantines are not looking south, but we know better – in this post, it’s still 614 and Muhammad is preaching in Mecca. But time will march forward, and Muhammad will march from Mecca to Medina. A new world is on it’s way, even if the Byzantines and Persians aren’t quite aware of it yet.

For Part II, see here.

[1] There are lots of particularities about the theology of the Church of the East not represented here. Understanding of the Church of the East’s theology have been hampered by issues in translation of the Syriac words used that have a different range than both their use by Syriac Miaphysites and the Greek/Latin “equivalents”. In recent years, the Church of the East has found some common ground with Catholic Christology. For more, see Sebastian Brock’s useful article “Nestorian, A Lamentable Misnomer” available here.

Leave a Reply